Content

- 1 Introduction: The Versatile Workhorse of Size Reduction

- 2 Fundamental Operating Principle: How Hammer Mills Work

- 3 Core Components and Design Variations

- 4 Primary Industrial Applications and Material Processing

- 5 Hammer Mill vs. Other Size Reduction Technologies

- 6 Critical Selection Guide: Choosing the Right Hammer Mill

- 7 Operation, Maintenance, and Safety Best Practices

- 8 The Future of Hammer Mill Technology

- 9 Conclusion: The Indispensable Engine of Particle Reduction

Introduction: The Versatile Workhorse of Size Reduction

In the vast landscape of industrial processing equipment, few machines match the rugged versatility and fundamental importance of the hammer mill. As a cornerstone technology for particle size reduction across countless industries, hammer mills transform bulk solid materials into uniform, usable granules through a straightforward yet highly effective mechanical process. From agricultural feed production and pharmaceutical powder processing to recycling operations and mineral preparation, these robust machines serve as primary or secondary crushers capable of handling an extraordinary variety of materials. This comprehensive guide examines the operational principles, design variations, key applications, and selection criteria for hammer mills, providing engineers, plant managers, and processing professionals with essential knowledge for optimizing their size reduction operations.

Fundamental Operating Principle: How Hammer Mills Work

At its core, a hammer mill operates on the principle of impact-based particle fracture. The size reduction process follows a systematic sequence:

-

Material Intake: Feed material is introduced into the grinding chamber through a controlled feed mechanism (gravity-fed hopper, volumetric feeder, or screw conveyor).

-

Particle Impact: Rapidly rotating hammers (rectangular, reversible, or swing-mounted metal pieces) attached to a central rotor strike the incoming particles with substantial kinetic energy.

-

Particle Fracture: The impact shatters brittle materials along natural fracture lines or shears and tears fibrous substances.

-

Secondary Reduction: Particles are further reduced as they are thrown against the chamber's interior wear liners and collide with other particles.

-

Size Classification: Reduced material continues this process until it is small enough to pass through a perforated screen (or grate) that encircles part of the grinding chamber, determining the final maximum particle size.

-

Discharge: Sized material passing through the screen is discharged, typically by gravity or pneumatic conveyance, for collection or the next processing stage.

This high-speed, continuous impact milling process makes hammer mills exceptionally efficient for a wide range of materials, particularly those that are friable, abrasive, or fibrous.

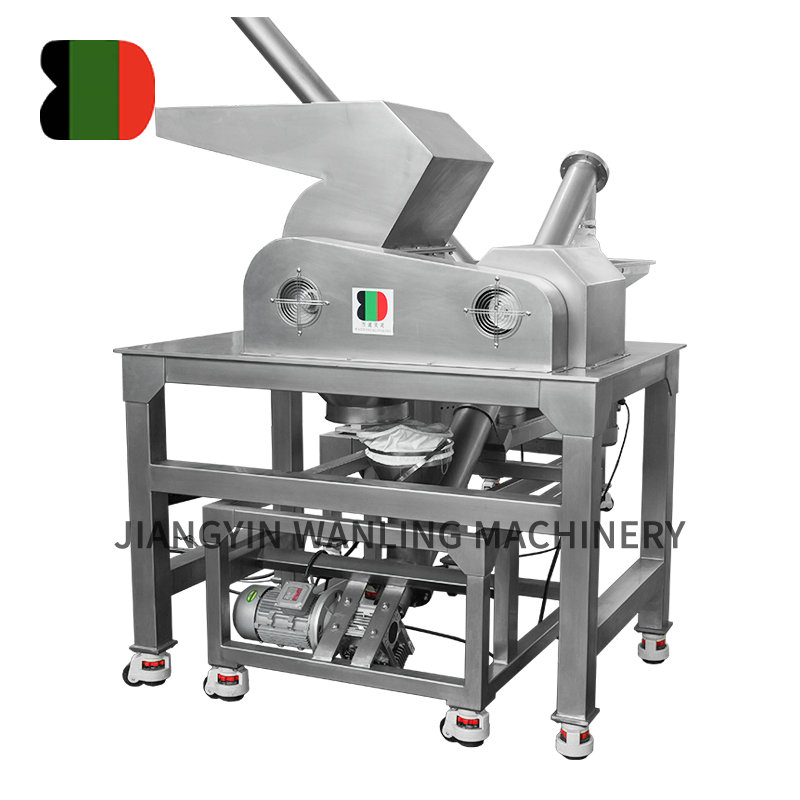

Core Components and Design Variations

The performance and application suitability of a hammer mill are determined by its specific design configuration.

1. Key Mechanical Components

-

Rotor Assembly: The heart of the machine. A heavy-duty steel shaft mounted on large bearings, carrying multiple rotor discs to which the hammers are mounted. Rotor speed (typically 1,800–3,600 RPM) is a critical variable.

-

Hammers: The active size reduction elements. Designs include:

-

Fixed (Rigid) Hammers: Bolted directly to the rotor, offering maximum strength for the toughest materials.

-

Swing Hammers: Pivoted on pins, allowing them to swing outward as they rotate. This design absorbs shock from uncrushable objects, providing protection against damage.

-

Reversible Hammers: Can be flipped to utilize a second, sharp edge, doubling service life before replacement or sharpening is needed.

-

-

Grinding Chamber & Liners: The enclosed housing where size reduction occurs. It is fitted with replaceable wear plates or liners (often made of AR400 steel or manganese) to protect the housing from abrasive wear.

-

Screen (Grate): The sizing device. Screens with precisely sized circular or slotted perforations encircle 180–300 degrees of the rotor. The screen hole diameter directly controls the maximum particle size of the discharged product.

-

Feed Mechanism: Can be top-, bottom-, or side-fed depending on the application and material characteristics.

-

Drive System: Typically consists of an electric motor connected via V-belts and sheaves to the rotor shaft. This allows for some speed adjustment by changing pulley sizes.

2. Major Design Configurations

-

Gravity-Discharge Mills: The simplest design. Reduced material falls through the screen by gravity. Best for fine grinding of lightweight, non-abrasive materials.

-

Pneumatic-Discharge Mills: Incorporates a powerful air suction fan at the discharge. This creates negative pressure in the chamber, improving throughput, cooling the product, and enhancing screen efficiency, especially for fine grinding (<100 microns).

-

Full-Circle Screen Mills: Feature a 300-degree screen, maximizing screen area for a given rotor diameter. This configuration dramatically increases throughput for applications involving fine grinding or grinding of fibrous materials like wood chips or biomass. The large screen area prevents clogging.

-

Industrial vs. Laboratory Scale: Industrial mills are heavy-duty, high-horsepower units for continuous operation. Laboratory-scale mills are benchtop units used for product development, feasibility testing, and small-batch production.

Primary Industrial Applications and Material Processing

Hammer mills are ubiquitous due to their adaptability. Key application sectors include:

-

Agriculture & Animal Feed Production: The largest application area. Used for grinding grains (corn, wheat, soybeans), oilseed cakes, and fibrous ingredients to create uniform animal feed. The ability to control particle size is critical for animal digestion and feed pellet quality.

-

Biomass & Biofuel Processing: Essential for size reduction of wood chips, agricultural residues (straw, husks), and dedicated energy crops before pelletizing or briquetting. Full-circle screen mills are standard here.

-

Food Processing: Used for grinding spices, sugar, dried vegetables, and food powders where sanitary design (often with stainless steel construction) is paramount.

-

Pharmaceutical & Chemical Industries: For fine milling of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and chemical powders. Designs focus on containment, cleanability, and precise particle size control, often with specialized hammer tips and screens.

-

Recycling & Waste Processing: Crucial for shredding electronic waste (e-waste), municipal solid waste, plastics, and metals for downstream separation and recovery. These are often heavy-duty "shredder" or "hog" hammer mills.

-

Minerals & Mining: Used for crushing and pulverizing coal, limestone, gypsum, and other moderately abrasive minerals.

Hammer Mill vs. Other Size Reduction Technologies

Selecting the right mill requires understanding the alternatives. Here’s how hammer mills compare:

| Equipment | Mechanism | Best For | Limitations / Not Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hammer Mill | Impact / Attrition (High-speed hammers) | Versatile friable materials, fibrous materials, aggregates. Wide particle size range (from coarse to fine). | Highly abrasive materials (high wear), heat-sensitive materials (can generate heat), very hard materials (>Mohs 5). |

| Jaw Crusher | Compression (Fixed & moving jaw plates) | Primary crushing of very hard, abrasive materials (rock, ore). Large feed size reduction. | Produces a relatively coarse product with many fines. Not for final fine grinding. |

| Ball / Rod Mill | Impact & Attrition (Tumbling media) | Wet or dry fine/ultra-fine grinding of ores, ceramics, paints. Very fine, uniform product. | High energy consumption. Slow process. Not for fibrous materials. |

| Pin Mill | Impact (Stationary & rotating pins) | Fine grinding of softer, non-abrasive materials (foods, chemicals). Lower heat generation. | Cannot handle large feed sizes or fibrous/stringy materials. |

| Knife Mill / Shredder | Shear / Cut (Rotating knives) | Fibrous, tough, stringy materials (tires, plastics, wood, municipal waste). Produces a shredded, flake-like product. | Not for fine powder production or friable materials. |

Critical Selection Guide: Choosing the Right Hammer Mill

Selecting and sizing a hammer mill requires a detailed analysis of both the material and process goals.

1. Material Characterization (The Most Important Step):

-

Hardness & Abrasiveness: Measured by Mohs scale or abrasion index. Highly abrasive materials (like silica sand) will rapidly wear hammers and screens, requiring specialized hardened alloys and increasing operating costs.

-

Friability: How easily the material fractures upon impact. Friable materials (grains, coal) are ideal for hammer milling.

-

Moisture Content: High moisture (>15%) can lead to screen clogging and reduced throughput. May require heated air assist or a pre-drying step.

-

Initial & Target Particle Size (F80 & P80): The feed size and desired product size determine the reduction ratio and required energy input.

-

Heat & Explosion Sensitivity: Some materials (foods, chemicals) degrade with heat or are explosible (dust). May require a mill with cooling features or explosion-proof construction (NFPA/ATEX).

2. Performance & Operational Specifications:

-

Required Capacity (Throughput): Stated in tons per hour (TPH) or kilograms per hour (kg/hr). This is the primary driver for machine size and motor horsepower.

-

Horsepower (HP/kW): Directly related to capacity and reduction ratio. Under-powering a mill leads to poor performance and clogging. A basic rule is 1–10 HP per TPH, depending on material and fineness.

-

Rotor Speed: Higher speeds (3,000+ RPM) generate more impacts for finer grinding. Lower speeds (1,800 RPM) provide greater torque for coarse grinding or tough materials.

-

Screen Area & Hole Size: Larger screen area increases capacity. The screen hole diameter should be 1.5–2 times smaller than the desired final particle size due to the elliptical shape of exiting particles.

3. Construction & Special Features:

-

Material of Construction: Carbon steel is standard. 304 or 316 Stainless Steel is required for food, pharmaceutical, or corrosive applications.

-

Safety & Access: Look for 360-degree screen access doors for easy screen changes and maintenance. Mills should have safety interlocks that cut power when doors are open.

-

Dust Containment: Fully sealed designs with flanged inlets/outlets are necessary for dust-free operation and integration with dust collection systems.

Operation, Maintenance, and Safety Best Practices

Proper operation ensures efficiency, longevity, and operator safety.

-

Start-up Sequence: Always start the mill empty and under the motor's full-load amperage (FLA). Begin feeding material only after the rotor reaches full operating speed.

-

Optimization: Product fineness is controlled by: 1) Screen Size, 2) Hammer Tip Speed, 3) Feed Rate. A finer screen, higher speed, or slower feed rate produces a finer product.

-

Preventive Maintenance Schedule:

-

Daily: Check for unusual vibration or noise. Inspect hammers for wear.

-

Weekly: Check drive belt tension and screen integrity for holes or clogging.

-

As Needed: Rotate or replace hammers when the leading edge is worn down (typically after 200–1000 hours, depending on material). Always replace or rotate hammers in complete sets to maintain rotor balance.

-

Periodically: Replace wear liners and screen sections. Check and lubricate bearings according to manufacturer specs.

-

-

Critical Safety Protocols:

-

Never open inspection doors while the rotor is in motion.

-

Use lockout/tagout (LOTO) procedures for all maintenance.

-

Ensure proper guarding is in place for all rotating parts and drive systems.

-

Be vigilant for ferrous metal contamination in feed material (tramp metal), which can cause severe sparks and damage. Use magnetic separators or metal detectors in the feed line.

-

The Future of Hammer Mill Technology

Innovation continues to enhance efficiency, durability, and control.

-

Advanced Materials & Coatings: Use of tungsten carbide overlays and ceramic composites on hammer tips and liners to extend service life in abrasive applications by 300–500%.

-

Smart Monitoring & Industry 4.0: Integration of vibration sensors, thermal imaging cameras, and power draw monitors to predict maintenance needs (predictive maintenance), optimize feed rates in real-time, and prevent catastrophic failures.

-

Design Optimization via CFD: Computational Fluid Dynamics is used to model air and particle flow within the grinding chamber, leading to designs that improve efficiency, reduce turbulence, and lower energy consumption per ton of product.

-

Noise Reduction Engineering: Improved chamber designs, sound-damping materials, and enclosures to meet stricter workplace noise regulations.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Engine of Particle Reduction

The hammer mill stands as a testament to efficient, practical engineering. Its simple, impact-based principle, when executed in a robust and well-designed machine, solves a fundamental industrial challenge across a breathtakingly diverse set of industries. Successful implementation, however, hinges on a deliberate selection process that carefully matches the mill's design parameters—rotor speed, hammer configuration, screen area, and horsepower—to the specific physical characteristics of the feed material and the desired product specifications.

By understanding the core principles outlined in this guide, engineers and operators can move beyond treating the hammer mill as a black box. Instead, they can leverage it as a tunable tool, optimizing it for maximum throughput, minimal wear cost, and consistent product quality. From processing the food we eat and the medicines we rely on to recycling the materials of modern life and producing sustainable biofuels, the hammer mill remains an indispensable and evolving workhorse at the heart of global industry.

Español

Español